I’m writing this in Kolkata, from a monstrosity of a luxury hotel located on the outskirts of the Southern part of the city.

I’m here, with my brother, to commemorate the one year death anniversary of my grandfather. In all honesty, I don’t think I processed the grief from my grandfather’s passing last year. I was preoccupied with my own personal and professional struggles, and went from sadness straight to acceptance as a way to keep myself sane.

The truth is, my grandfather was largely responsible for my connection to this city. It’s through his anecdotes, meandering stories and evenings of doing adda that I pieced together the significance of this city for my family’s lineage and ultimately, for me.

Without him, I’m not sure I would’ve developed the depth of appreciation and understanding of Bengali culture, food, people, psyche and so many other things. It was that depth that led to us creating Kolkata Chai and building a behemoth of a brand through nothing but our memories and an iPhone.

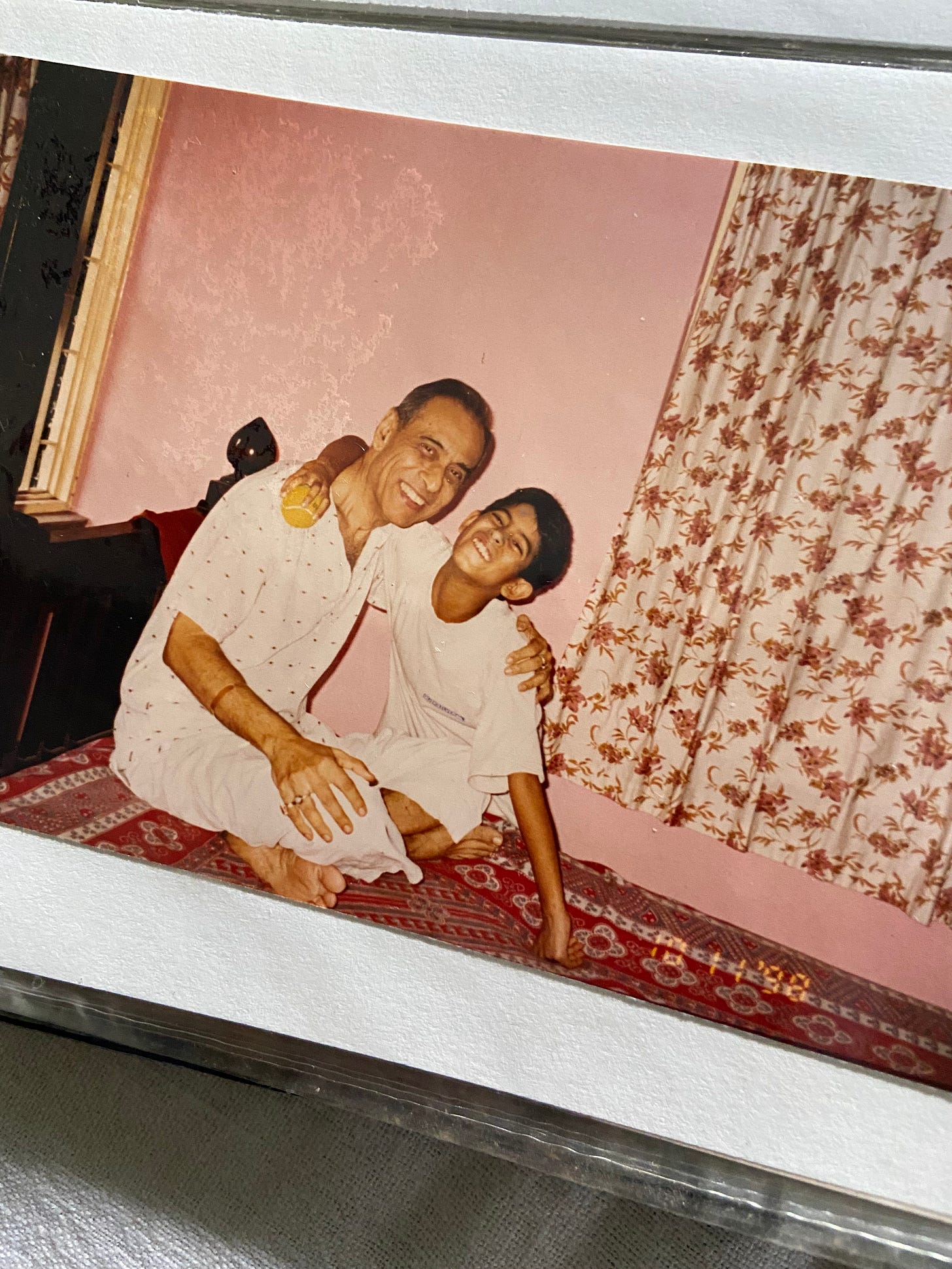

This story starts in the summer of ’96. I was eight years old, and my mother had taken us to spend a few months Kolkata. It was a quintessential Indian summer — the heat was stifling, the crows were raucous and the city seemed to move at the speed of molasses.

Our trip happened to coincide with the World Cup of Cricket, aptly being hosted on the subcontinent for the first time in decades. I can only imagine my grandfather’s position, sizing me up as his American-born, French fry eating grandson, who could potentially have a massive disdain for anything cultural. Why would I care about cricket? He had heard the ‘horror’ stories of my mother’s NRI sons coming to Kolkata and eating nothing but Pringles for the entire time they were there. But that wasn’t how I was raised.

I became engrossed with cricket. Seeing brown men competing athletically was nothing something I was used to growing up in America. We were relegated to being the butt of jokes as convenience store owners and spelling bee champs. Though cricket was new to me, I would pull up to the 16” inch TV every afternoon, swatting at the mosquitoes around my ankles, to watch team India take on teams from around the world. This was a time when the legendary Sachin Tendulkar was in peak form and I was enraptured. My grandfather, surprised by my interest in the sport, would pull up next to me, eschewing his customary afternoon nap to watch the matches with me.

He would explain all the rules and nuances I was missing, and tell me about all reasons why Team India was the permanent underdog in the tournament. Whenever someone on the team would do something suboptimal, he would come up with a string of comedic slurs, bashing the player and their entire family for dropping a catch or missing a runout. I would not be able to control my laughter, and we spend our evenings yelling, praying and cajoling the Indian players through the screen to win the match.

That year started a decades long bond over life and cricket between my us. I would tell him of trips I took to the UK, spending 18 hours in London just to watch India play before heading back to my Monday meeting in New York. He would update me on the new talent that was taking over the reins on team India, as our favorite players like Sourav Ganguly (a Kolkata-born Bengali, and one of the few that have ever reached that level of success) retired or moved on from the game.

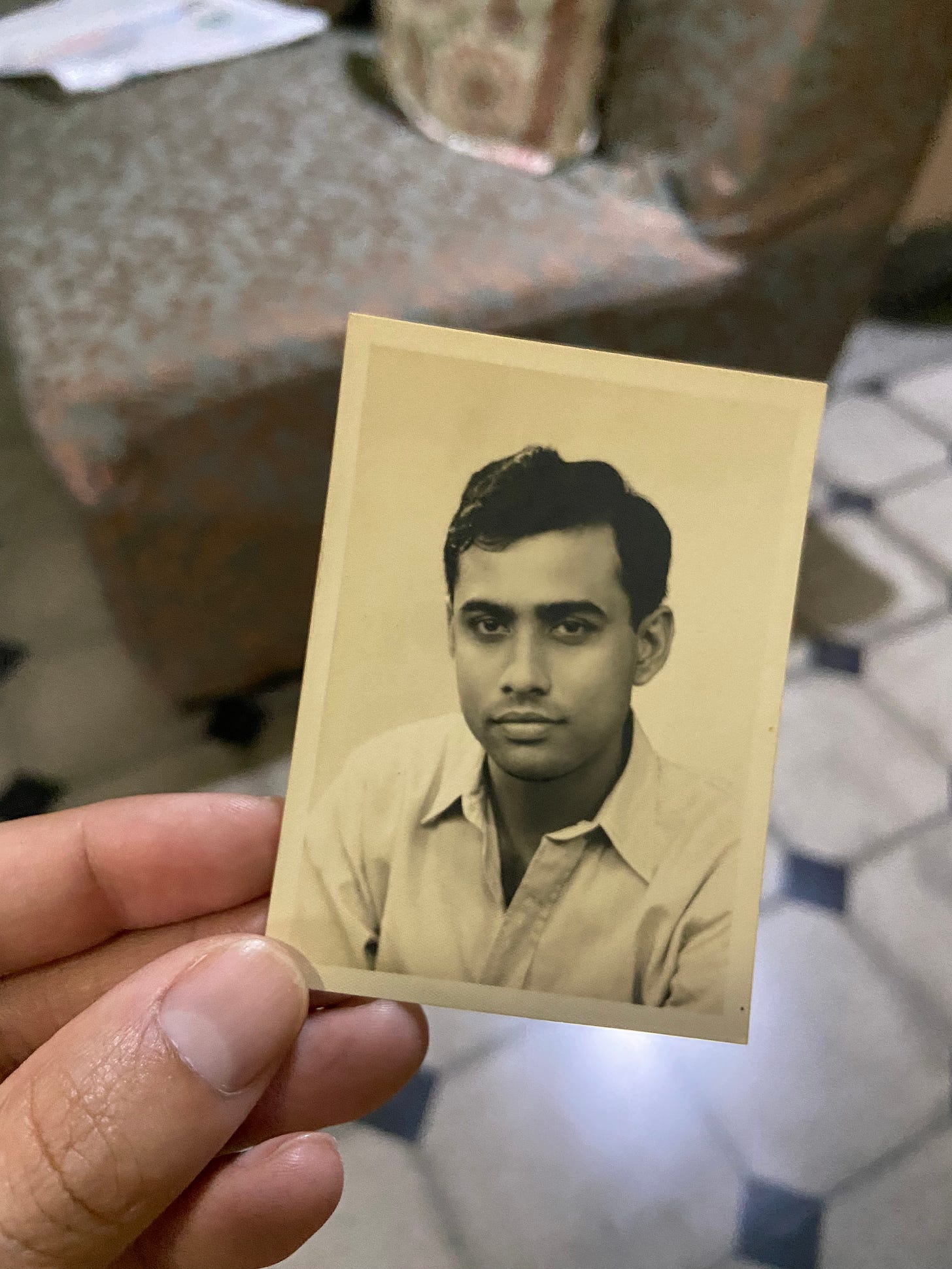

My love for cricket spawned into my love for Kolkata and Bengali culture. Unadulterated, hopeful, etc. On later trips, I would accompany my grandfather for walks around his neighborhood of Maddox Square, as he would expound on the rich history of his family, friends and upbringing that wove the rich tapestry of his community. He simplified the world for me — he wasn’t into money or any of the trappings as a way to signify the progress he had made in life. He was content because he was surrounded by family, love and life’s most essential, simple pleasures. He loved a good cologne, a wool scarf for the winters and making sure his prized home, the one he inherited from his father, was always in spotless condition.

When we opened Kolkata Chai in 2018, he was elated and would effusively share our successes with his neighborhood friends. When his favorite newspaper, the Statesmen, did an article about us after opening, he called us (despite barely knowing how to use his mobile phone) to read the entire article in his booming, British English style, his words dripping of pride and joy. I recorded a video of this conversation as one of my favorite moments of my life. He couldn’t believe his two grandsons had honored his hometown in the way we had — authentically, uncompromised and as an honest reflection of our own experiences.

When people laud the “authenticity” behind KCC or the immaculate balance we’ve created between traditional and modern, I hold back from sharing the real reasons for that. That “authenticity” isn’t a branding technique — rather, it’s from real lived experiences of walking the streets of South Kolkata with my grandfather, going to the fish markets to pick his favorite bhetki, watching cricket into long hours of the night or packing into his tiny Maruti to go eat indo-chinese at the Calcutta Club.

Nothing will fill the void of him not being here. I had so much to share with him this time around — about the thousands of people who visit a placed called “Kolkata Chai” every month to drink masala chai and do their form of “adda”. I wanted to find a way to fly him to NYC to experience it for himself, but unfortunately we ran out of time.

Though he is not with us on this physical plane, I hope he can see it all from his perch somewhere. I hope he can feel the intensity with which Ayan and I pursue this path, to honor our family, our values and reframe the city of Kolkata for the rest of the world as a place of unending flavor, love and real human experiences.

Over the past few years, my grandfather and I would joke on the phone about his age and how he was “still batting” — a cricket term of still being alive on the pitch. “I am 88 not out,” he would lament, a reference to his age and his ability to still keep living. I would respond that I needed him to get a century, or make it to a 100 years, and we would both laugh. Though he didn’t quite make it there, I take solace in the fact that he lived a full life and left an indelible impact on everyone in his orbit.

To my dadu, Mr. Ambarish Ghatak, thank you for everything. You will always be my choice for Man of the Match, today and forever.